On one of our recent forays to the library, Isabel and I picked up a book that reads like a classic fairy tale, though it was written in 1987. It's gripping, a little creepy, gorgeously illustrated, and possessed of the kind of fairy tale logic and threat level I associate with Grimm Brothers stories. I actually had to do a little research on it to confirm for myself that it's a contemporary story, not a retelling of something older.

The book is called Heckedy Peg, by Audrey Wood, illustrated by Don Wood. They're a married couple, and a writing/illustrating team we know well from the awesome book of opposites Quick as a Cricket, which I can still recite verbatim after reading it a thousand times to Eleanor in her first couple of years. I think the Woods are best known for The Napping House and King Bidgood's in the Bathtub, both of which are energetic and light-hearted, and play with repetition ("King Bidgood's in the bathtub, and he won't get out!").

The book is called Heckedy Peg, by Audrey Wood, illustrated by Don Wood. They're a married couple, and a writing/illustrating team we know well from the awesome book of opposites Quick as a Cricket, which I can still recite verbatim after reading it a thousand times to Eleanor in her first couple of years. I think the Woods are best known for The Napping House and King Bidgood's in the Bathtub, both of which are energetic and light-hearted, and play with repetition ("King Bidgood's in the bathtub, and he won't get out!").Heckedy Peg is darker, in fairy tale form. It's the story of a poor mother who lives with her seven children, named after the days of the week (Monday, Tuesday, etc.). Before going off to market one day, she asks the children what each of them would like as a present:

Monday asked for a tub of butter.

Tuesday asked for a pocket knife.

Wednesday asked for a china pitcher.

Thursday asked for a pot of honey.

Friday asked for a tin of salt.

Saturday asked for crackers.

And Sunday asked for a bowl of egg pudding.

The mother goes off, telling her children not to let any strangers in and not to touch fire. Of course, as soon as she's gone, the witch Heckedy Peg comes to the house:

I'm Heckedy Peg.

I've lost my leg.

Let me in!

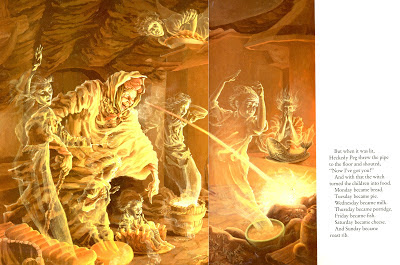

After a brief back and forth, she convinces the children to let her in and light her pipe with fire from the hearth. As soon as they do, she turns them into food (the illustration here is fabulously ghostly):

The mother returns home to find her children gone, and the story becomes about her quest to get them back. She tricks Heckedy Peg into letting her in by pretending to cut off her own feet (you see what I mean about the Grimm aspect here), and the witch gives her a chance to break the spell: if she can correctly identify which child is which food on her first try, she wins them all back. She uses the gifts each child wanted to figure it out:

Bread wants butter. That's Monday.

Pie wants knife. That's Tuesday.

Milk wants pitcher. That's Wednesday.

Porridge wants honey. That's Thursday.

Fish wants salt. That's Friday.

Cheese wants crackers. That's Saturday.

And roast rib wants egg pudding. That's Sunday.

The children resume their natural forms (Sunday, the littlest, immediately starts eating his bowl of egg pudding), and the mother emerges triumphant and runs the witch off.

It's pretty awesome.

I love the mother in this book, for her strength and her ultimate knowledge of her children. I think Isabel responds to the odd magic of it, and the fairy tale trope of having disaster befall you when you break the rule you've been set. The illustrations are spectacular -- the kids full of life in the pictures of their playful moments, every picture clearly a portrait of a real person. It's a book with real staying power.

Love, Annie