Once there was a little girl who didn't understand about time. She was so little that she didn't know about Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday. She certainly didn't know about January, February, March, April, May, June, July, August, September, October, November, December. She was so little she didn't even know summer, winter, autumn, spring.

What she did know about was all mixed together. She remembered a crocus once, but she didn't know when. She remembered a snowman and a pumpkin, and a Christmas tree, and a birthday cake, a Thanksgiving dinner and valentines. But they were all mixed up in her mind.

Dear Annie,

That's the beginning of Over and Over by Charlotte Zolotow (illustrated by Garth Williams), explaining the rhythms of a year. Zolotow died this past week, at the age of 98. She wrote more than 70 picture books, and edited countless other children's books. They have a gentle straightforward tone to them -- they feel a little old-fashioned but still very in touch with kids' feelings.

My favorite is Mr. Rabbit and the Lovely Present, a lovely discussion between a girl and a rabbit (illustrated by Maurice Sendak) about what she should get for her mother's birthday. It, too, starts wonderfully:

"Mr. Rabbit," said the little girl, "I want help."Mr. Rabbit suggests several different colors, which get narrowed down to objects (red > red underwear > red roof > red bird > red apple) until the girl ends up with a basket of fruit for her mother. It's idiosyncratic and lyrical.

"Help, little girl, I'll give you help if I can," said Mr. Rabbit.

"Mr. Rabbit," said the little girl, "it's about my mother."

"Your mother?" said Mr. Rabbit.

"It's her birthday," said the little girl.

"Happy birthday to her then," said Mr. Rabbit. "What are you giving her?"

"That's just it," said the little girl. "That's why I want help. I have nothing to give her."

"Nothing to give your mother on her birthday?" said Mr. Rabbit. "Little girl, you really do want help."

Zolotow wrote the iconic (but kinda archaic) William's Doll about a boy who's teased for wanting a doll. It became rooted in the psyches of a whole generation (not mine -- was it yours?) who grew up listening to Free to Be You and Me.

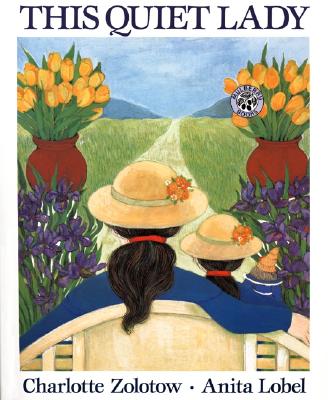

This Quiet Lady was a favorite in our house. Anita Lobel's illustrations underscore the intimacy of a child exploring pictures of her mother's childhood. I was always partial to the drawing of a 10 year-old mom going off to school with a Beatles lunchbox. It was rooted enough in its era that it eventually became outdated: the Beatles belong to grandma now.

Every now and then I'll be reminded of another special book that Zolotow wrote. A woman who really cared about communicating with children. Her daughter, Crescent Dragonwagon has also produced dozens of kids' books.

Here's a little bit of the L.A. Times obituary:

. . . a few days before she died she stopped eating and drinking.

"She lived a full life and it was like, she had been at the party, and now it was time to take off her shoes," Dragonwagon said.

One of Zolotow's last published books was 1997's "Who Is Ben?" about a boy asking questions about his existence. Dragonwagon said she might read from it at a memorial for her mother.

"The boy asks, 'Why does the day end?' " Dragonwagon said, "and his mother tells him that it doesn't end, it goes on to become day somewhere else."

Love,

Deborah